Some days ago we published the review of “Three parts dead” by Max Gladstone and today we bring you an interview with him. The interview is very interesting, hope you enjoy it!. You can read this entry in Spanish.

When did you know you wanted to become a writer? Which other authors have influenced you? Is there any current writer that you admire?

Right in with the easy questions, I see! I’ve always loved storytelling. Writing has let me tell stories at my pace, which is fast. I was trying to write before I could talk—my parents remember me scribbling inside the lines of their notebooks. My first favorite toy was a toy car, but my next was an old travel typewriter. I loved the feeling of striking keys.

As for author influences, Roger Zelazny is a huge one. I’ve read his book “Lord of Light” about twenty times, and basically everything else he’s written, though I’m still working my way through his short fiction. Other immensely important writers for me growing up include Robin McKinley, Ursula K Leguin, Dorothy Dunnett, and, honestly, William Shakespeare.

As for current writers—some of the writers on the list above still live, so they count. Also, while I didn’t find John Crowley‘s writing until college, when I did, it impressed me immensely. “Little, Big” is both The Great American Novel and The Great American Fantasy Novel. I don’t know anyone else who can make that claim.

Why did you choose to study Chinese? What can you tell us about your life there, especially in the Xiuning Middle School?

I started to study Chinese because, after a trip there in high school to study taiji, I was awed by the sheer amount of material there was to the language and culture. I could study it for my entire life and barely scratch the surface. What I didn’t really understand at the time, was that I could study it my entire life and barely scratch the surface! Fortunately I learned some amazing things in the process of barely scratching the surface.

Xiuning Middle School is a tiny magnet middle school in the middle of southern Anhui, which is tea country. The village across the street from the middle school had a few hundred people, and the nearest larger town was about ten minutes’ fast bike ride away. Outside of that, around us we had tea and canola fields, and water buffalo. Misty mountains in the distance. Chickens everywhere. Enterprising rats in the fields, Odin the One-eyed Cat guarding the trash heap behind the school, egret swarms in spring (chased off the school grounds by hirelings with illegal guns), Ming-dynasty watchtowers leaning over to fall, and of course classes full of some of the brightest young students who have ever been forced through a disgustingly intense standardized testing regime. Teachers struggling to teach under the same sick testing mandates. Communist Party officials hanging around challenging us to drinking contests. And wherever I went, being instantly recognized, since our arrival was televised—even if the Stars Align and I suddenly catapult to JK Rowling levels of success I never will be so singled out as I was on any given Xiuning streetcorner. Wherever I went in school, students following me with cries of “Hello, MAX!” Teaching students the Twist at New Year’s Eve parties. Hearing about kids’ hopes for their lives; introducing some to rock & roll. Coming home one day to find our house draped in banners and covered in graffiti saying ‘TIBET IS AN INDISPUTABLE PART OF CHINA.’ I could write books and books about those two years. Maybe one day I will.

Xiuning Middle School is a tiny magnet middle school in the middle of southern Anhui, which is tea country. The village across the street from the middle school had a few hundred people, and the nearest larger town was about ten minutes’ fast bike ride away. Outside of that, around us we had tea and canola fields, and water buffalo. Misty mountains in the distance. Chickens everywhere. Enterprising rats in the fields, Odin the One-eyed Cat guarding the trash heap behind the school, egret swarms in spring (chased off the school grounds by hirelings with illegal guns), Ming-dynasty watchtowers leaning over to fall, and of course classes full of some of the brightest young students who have ever been forced through a disgustingly intense standardized testing regime. Teachers struggling to teach under the same sick testing mandates. Communist Party officials hanging around challenging us to drinking contests. And wherever I went, being instantly recognized, since our arrival was televised—even if the Stars Align and I suddenly catapult to JK Rowling levels of success I never will be so singled out as I was on any given Xiuning streetcorner. Wherever I went in school, students following me with cries of “Hello, MAX!” Teaching students the Twist at New Year’s Eve parties. Hearing about kids’ hopes for their lives; introducing some to rock & roll. Coming home one day to find our house draped in banners and covered in graffiti saying ‘TIBET IS AN INDISPUTABLE PART OF CHINA.’ I could write books and books about those two years. Maybe one day I will.

What do you think of the current situation of science fiction and fantasy in China? I have read Cixin Liu’s short stories and think they’re great. Are there more authors that need to be translated?

Embarrassing confession time: I’m not very up on Chinese genre fiction outside of the great classics of Wuxia, the home-grown historical kung fu mythosphere that more than matches the Knights-and-Wizards Western European mythosphere for quantity and quality of writing. Genre is a cult of secret knowledge in all meridians—people rely on local masters (of whatever gender) to tell them what they should be reading. I never found someone to do that for me in China, so I’m restricted to the big names like Liu Cixin. If you find Jin Yong’s novels in translation, read them. There are good (and recently reworked) translations of Journey to the West, which if you’re a fantasy fan and you haven’t yet read I suggest you rectify that at your earliest opportunity. But modern stuff, I’m as in the dark as anyone. I appreciate any recommendations!

Embarrassing confession time: I’m not very up on Chinese genre fiction outside of the great classics of Wuxia, the home-grown historical kung fu mythosphere that more than matches the Knights-and-Wizards Western European mythosphere for quantity and quality of writing. Genre is a cult of secret knowledge in all meridians—people rely on local masters (of whatever gender) to tell them what they should be reading. I never found someone to do that for me in China, so I’m restricted to the big names like Liu Cixin. If you find Jin Yong’s novels in translation, read them. There are good (and recently reworked) translations of Journey to the West, which if you’re a fantasy fan and you haven’t yet read I suggest you rectify that at your earliest opportunity. But modern stuff, I’m as in the dark as anyone. I appreciate any recommendations!

Have you read Barry Hughart’s stories placed in China (such as Bridge of Birds)? What do you think about them?

I’ve only read “Bridge of Birds” a few months back, and I loved it so much I’m saving the rest for some day when I really, really need a good new book. Amazing. I have no idea how “Bridge of Birds” is as good as it is. It has no right to be. It’s a surprise and a gift. The only weakness I can think of is that it’s a little short on female characters, but for a book that revolves around boys, men, power, and growth, and the ways these things can inflict terrible damage on the world in general and women specifically, maybe that’s not a surprise. Anyway. He’s great.

How did you work with the idea of mixing magic, economy and law in “Three parts dead”?

With great difficulty!

No, seriously, they all go together so well. Law and economy is easy—there’s a whole school of legal thought called “law and economics” for that reason. And then, well, magic. On the one hand we have transactions of invisible power that affect the spiritual environment and rely on the faith of all those concerned, and on the other hand we have… economics. Meanwhile, law and magic both use dead languages (and ancient civilizations!), contracts, bargains, loopholes, confrontations, human sacrifice, and mountains upon mountains of books. They married quite well together.

Have you ever been contacted by some Spanish publisher to translate your books?

No, but I’m interested! Let me know!

What can you tell us about your new projects?

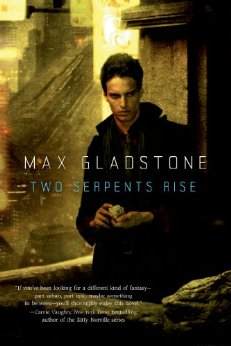

The next book, “Two Serpents Rise”, is set in the same world as “Three Parts Dead”. Decades after a desert city kicked out its gods, they’re struggling on the edge of survival. Someone’s poisoned their water supply, and Caleb, risk manager and descendant of the banished high priests, needs to figure out why, and stop them. Chinatown meets Legend of Korra in Aztec-influenced psudoLA. Kinda sorta.

The next book, “Two Serpents Rise”, is set in the same world as “Three Parts Dead”. Decades after a desert city kicked out its gods, they’re struggling on the edge of survival. Someone’s poisoned their water supply, and Caleb, risk manager and descendant of the banished high priests, needs to figure out why, and stop them. Chinatown meets Legend of Korra in Aztec-influenced psudoLA. Kinda sorta.

Are social networks important for you relationships with other authors and with your readers?

I like my social face to face, but I’m slowly learning the ropes of social media. The catch is that, of course, I want to spend most of my time writing—and twitter pings & the like do interrupt the flow.

Does fencing help you with action scenes?

Yes, ish. Fencing, like any martial art, controls its conditions. You’re on a ~2m wide strip, about 14m long, and your strikes score under particular circumstances—so if you try to craft realistic fight scenes with fencing as your sole referent, you’ll get a lot wrong. That said, fencing is a great way to learn the experiences of time dilation, of decision-making under pressure, of threat and compensation, ambition and danger, and the sleight-of-hand of combat, without actually going out and getting into fights. i’ve trained in a number of martial arts, and in some ways they’re all useful for action scenes, but only when I roll them together with the straight-up fistfights I got into as a kid, and the few-pads sparring I tried later.

I wish to thank again Max for his answers and recommend you his book “Three parts dead”.

UPDATE: Somehow we lost one question. Here it is.

How do you document yourself?

I use a lot of different sources when I’m researching a book. Wikipedia is a good start, but only if you know where to look, and even then, there’s a lot of context you can’t get from an article. I’m fortunate to live in a place with a great public library ILL system, which is a lifesaver for research projects; good used bookstores can also turn up surprising details and new bits of knowledge. Still, there’s a limit to the written word. At some point you have to talk to people. That’s the best way to get the story through their eyes.

2 respuestas a «Interview with Max Gladstone»