Ian Sales conoció personalmente al objeto de nuestro homenaje Iain Banks y ha sido tan amable de escribir para nosotros un post especial sobre él e incluso mandarnos una foto de su archivo personal. Me he permitido traducir su mensaje al español con la inestimable ayuda de Cristina Jurado.

Ian Sales conoció personalmente al objeto de nuestro homenaje Iain Banks y ha sido tan amable de escribir para nosotros un post especial sobre él e incluso mandarnos una foto de su archivo personal. Me he permitido traducir su mensaje al español con la inestimable ayuda de Cristina Jurado.

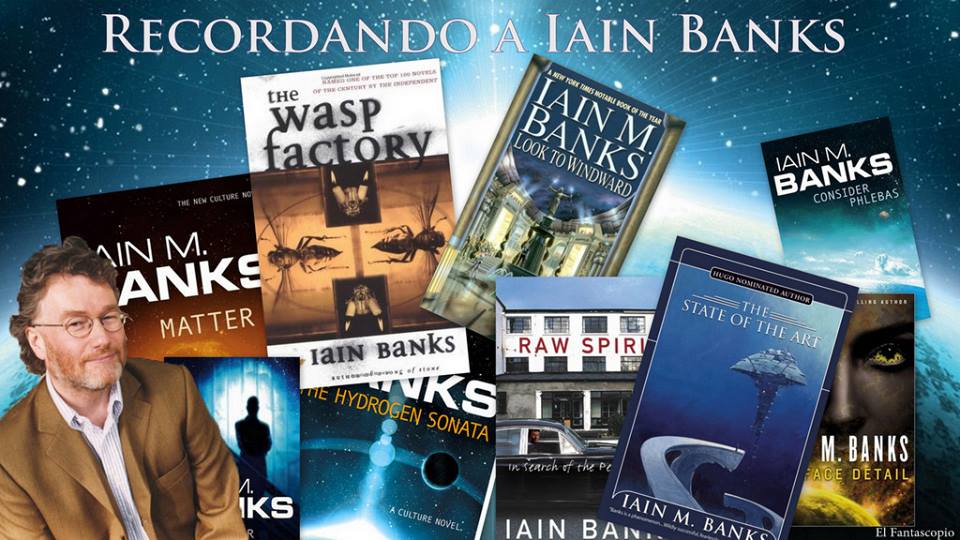

Iain Banks – My Part in his Success

I first encountered Iain Banks at university in 1986 – a housemate shoved a copy of “The Wasp Factory” at me and urged me to read it. So I did. As promised, it was sick and twisted and very, very good. In fact, parts of the book have remained with me to this day, which is testament to its quality. I remember reading some of his other novels soon afterwards – I especially liked “Espedair Street”. Then I joined the British Science Fiction Association, and learned he’d written a science fiction novel, “Consider Phlebas”.

In 1989, I went to my first science fiction convention – it was local and seemed like a good opportunity to see what a convention was like. I enjoyed it. Later that same year, I attended another, this time in Glasgow. Banks was the Guest of Honour. “Canal Dreams” had been published that year, and I recall the convention booklet describing it as a “taunt thriller” instead of a “taut thriller”. I also learned that Banks had quite a reputation – cat-burgling at the Hilton Metropole in Brighton, for example, was an oft-repeated story. It was, of course, based on a small incident that had been blown completely out of proportion. But such stories seemed to attach to Banks, as if he were larger than life, much as his science fiction was larger than the genre seemed capable of containing. I was even a witness to one addition to the Banks mythology at that Glasgow convention, when during a room party I saw him pretend to drink from a bottle of massage lotion.

During that time, Banks was a fixture at British science fiction conventions. I next saw him at the Eastercon in Liverpool in 1990. Use of Weapons was launched there, and I bought a copy and had it signed. The Observer magazine had published Banks’s story about the Lockerbie bombing, ‘Piece’, late the year before, so we all knew his star was definitely on the rise. But there was no bad feeling about this – if sf needed an ambassador to the wider world of literature, then Iain Banks was well-qualified for the job. During the con, Chris Reed of Back Brain Recluse magazine arranged an interview with Banks, but couldn’t find anywhere quiet enough to do it – so I volunteered my hotel room. Around a dozen of us sat around and listened to Banks as he talked about Lockerbie, bridges, women’s underwear and science fiction. As far as I know, the interview has never been published.

During that time, Banks was a fixture at British science fiction conventions. I next saw him at the Eastercon in Liverpool in 1990. Use of Weapons was launched there, and I bought a copy and had it signed. The Observer magazine had published Banks’s story about the Lockerbie bombing, ‘Piece’, late the year before, so we all knew his star was definitely on the rise. But there was no bad feeling about this – if sf needed an ambassador to the wider world of literature, then Iain Banks was well-qualified for the job. During the con, Chris Reed of Back Brain Recluse magazine arranged an interview with Banks, but couldn’t find anywhere quiet enough to do it – so I volunteered my hotel room. Around a dozen of us sat around and listened to Banks as he talked about Lockerbie, bridges, women’s underwear and science fiction. As far as I know, the interview has never been published.

I remember reading “Use of Weapons” several months after the convention and being blown away by its clever structure and ending. Iain Banks has often been credited with kicking off the British New Space Opera wave, and novels like “Use of Weapons” make it easy to understand why.

That year, Banks seemed so ubiquitous in the genre press that I put “SPECIAL ISSUE: NO IAIN BANKS INTERVIEW” on the cover of a fanzine I edited. I showed him a copy at the 1991 Eastercon in Glasgow, and he signed the fanzine for me. I’ve since lost the copy, which is a shame.

In 1996 – I was living in the Middle East by then – I returned to the UK on holiday, as I did each year, and at a convention in Birmingham bought “Excession”. Banks was present, so he signed it for me. I think it was at that convention where we had the bar conversation in which we tried conflating the opening lines from his “The Crow Road”, “It was the day my grandmother exploded”, and John Varley’s “Steel Beach”, “‘In five years, the penis will be obsolete,’ said the salesman”. The results are probably unprintable.

From that point on, I bought each new novel by Iain Banks in hardback as it was published. He became a fixture of my reading each year. If I was disappointed by any of his novels, it was only because I had such high expectations of them. And yet, even in the most disappointing of his books, he usually managed to rise to those expectations at some point – and occasionally, he would even exceed them. I loved his books for his voice, his wit, the fact that his science fiction novels were more than just adventure stories in outer space, despite their bright candy-coloured visuals and vast panoramas. Though I’d only met him a handful of times, he felt like a friend and reading his novels felt like a conversation with him.

When I started a blog in 2007, I wrote about Banks’s new sf novels as I read them – he’s the only author I’ve ever done that for. I think the Culture is one of British science fiction’s great achievements, and Banks’s Culture novels an excellent series – although, perversely, my favourite of his sf novels, “Against A Dark Background”, isn’t one of them.

Iain Banks often seemed like the face of British science fiction, especially to someone who was active in fandom – attended conventions, read UK genre magazines, and corresponded with other British sf fans. Banks wrote space opera that was highly-regarded by sf fans, but he also wrote best-selling literary fiction (his literary fiction outsold his sf, he admitted, “by a ratio of about three or four to one”). He had proven that it was possible to be taken seriously as a writer – and so, by association, a reader – of science fiction. Non-genre readers had heard of him, and some were even aware he also wrote science fiction. He had broken down the wall of the ghetto.

It would have been nice if others had followed Banks lead, but sadly no one did. While JG Ballard did drift into literary fiction, he also deliberately distanced himself from his genre beginnings. I can’t offhand think of another UK genre writer who has books published both by a genre imprint and by a literary imprint. Many have blurred the lines, but no one but Banks has so comprehensively trampled it into the dirt. Some people were fans only of his sf, some only of his literary fiction, but many – and I count myself among these – were fans of all his books.

Iain Banks left behind him an enviable body of work, and I suspect many of his novels will remain in print for a long time. It has been a number of years since I last read some of his books, and I certainly plan to reread them again soon. I suspect I may well end up rereading them a number of times over the years.

Iain Banks – Mi parte en su éxito

Me encontré por primera vez a Iain Banks en la universidad en 1986. Un compañero de piso me dio una copia de “The Wasp Factory” y me animó a leerla, así que lo hice. Como me había prometido, era retorcida y enferma y muy, muy buena. De hecho, hay fragmentos del libro que han permanecido conmigo hasta el día de hoy, lo cual da prueba de su calidad. Recuerdo haber leído alguna de sus novelas poco después – me gustó especialmente “Espedair Street”. Después me uní a la British Science Fiction Association y así me enteré de que había escrito una novela de ciencia ficción “Consider Phlebas”.

En 1989 acudí a mi primera convención de ciencia ficción. Era un evento local y parecía una buena oportunidad para ver cómo era una convención por dentro. La disfruté. Ese mismo año acudí a otra, esta vez en Glasgow. Banks era el invitado de honor. Acababa de publicar “Canal Dreams”, y recuerdo que el folleto de la convención lo describía como un “taunt thriller” (thriller de burla) en vez de un “taut thriller” (thriller tenso). También supe que Banks tenía cierta reputación: una de las historias que más se repetían sobre él hablaba de cómo solía colarse en el Hotel Hilton Metropole de Brighton. Esa leyenda urbana estaba basada en un pequeño incidente que se había magnificado, pero esas historias parece que perseguían a Banks -como si él mismo fuera más grande que la vida- de la misma forma que su propia ciencia ficción era más grande de lo que el género parecía poder abarcar. Incluso fui testigo de una nueva muestra de la mitología Banksiana en la convención de Glasgow: durante una fiesta le vi hacer como que bebía de una botella de crema para masajes.

Por aquel entonces Banks era un personaje fijo en las convenciones británicas de ciencia ficción. La siguiente vez que le vi fue en la Eastercon en Liverpool, en 1990. “Use of Weapons” se lanzó allí y compré un ejemplar para que me lo firmara. The Observer había publicado “Piece”, la historia de Banks sobre el atentado de Lockerbie, a finales del año anterior, así que todos sabíamos que era una estrella en alza. Pero no había sentimientos encontrados al respecto. Si la ciencia ficción necesitaba un embajador en el mundo de la literatura, Iain Banks estaba bien preparado para el trabajo. Durante la convención, Chris Reed de la revista Back Brain Recluse quiso entrevistarlo, pero no encontró ningún lugar adecuado para hacerlo y yo ofrecí mi habitación. Una docena de personas asistimos a la entrevista y escuchamos a Banks hablar sobre Lockerbie, puentes, ropa interior de mujer y ciencia ficción. Por lo que sé, esa entrevista nunca se publicó.

Recuerdo leer “Use of Weapons” meses después de la convención y quedar maravillado por su inteligente estructura y su final. A menudo se le ha acreditado por haber dado el pistoletazo de salida a la British New Space Opera, y novelas como “Use of Weapons” hacen fácil entender por qué.

Aquel año Banks aparecía tan asiduamente en la prensa de género que creé una portada especial del fanzine que editaba titulada “SPECIAL ISSUE: NO IAIN BANKS INTERVIEW”. Le enseñé una copia en 1991 en la Eastercon de Glasgow y me la firmó. He perdido esa copia, lo cual es una lástima.

En 1996 – por aquel entonces yo vivía en Oriente Medio- volví al Reino Unido de vacaciones, como hacía cada año, y en una convención en Birmingham compré Excession. Banks estaba presente, así que lo firmó. Creo que fue en esa convención donde mantuvimos aquella conversación tabernera en la que intentamos conjugar las primeras líneas de su “The crow road” (“It was the day my grandmother exploded”), y de “Steel Beach” de John Varley, (“In five years, the penis will be obsolete, said the salesman”). Los resultados de aquel encuentro son probablemente impublicables.

Desde entonces he comprado cada nueva obra de Iain Banks en tapa dura en el momento de su publicación. Se convirtió en un fijo en mis lecturas de cada año. Si alguna de sus novelas no me convencía, era solo porque mis expectativas sobre ellas eran muy altas. Y aún en los menos atractivos de sus libros, se conseguía colmar esas expectativas en algún punto, en ocasiones, incluso superarlas. Amaba sus libros por su voz, su inteligencia, el hecho de que sus novelas de ciencia ficción fueran algo más que meras historias de aventuras en el espacio, a pesar de sus brillantes imágenes de colores pastel y sus vastos panoramas. Aunque solo coincidí con él en unas cuantas ocasiones, sentía que era un amigo, y leer sus novelas era como mantener una conversación con él.

Cuando empecé un blog en 2007, escribía sobre las nuevas novelas de ciencia ficción de Banks conforme las iba leyendo. Es el único autor con el que lo he hecho. Creo que la Cultura es uno de grandes logros de la ciencia ficción británica y las novelas de la saga son una serie excelente aunque, de un modo perverso, mi novela favorita de género de Banks es “Against A Dark Background”, que no pertenece a la serie.

A menudo Iain Banks parecía ser la cara de la ciencia ficción británica, especialmente para alguien que fuera activo en el fandom, yendo a convenciones, leyendo revistas británicas de género y manteniendo correspondencia con otros fans de las islas. Escribía space opera que estaba muy bien considerada por los fans del género, pero también escribía best-sellers de ficción literaria (su producción en este campo vendía tres o cuatro veces más que su ciencia ficción). Demostró que era posible ser tomado en serio como escritor (y por asociación, como lector) de ciencia ficción. Incluso quienes no leían género habían oído hablar de él, y algunos incluso sabían que escribía también ciencia ficción. Derribó el muro del gueto.

Hubiera sido bonito si otros hubieran seguido su camino, pero tristemente nadie lo hizo. Mientras que JG Ballard se inclinó hacia la ficción literaria, también se distanció deliberadamente de sus inicios en el género. Ahora mismo no se me ocurre otro escritor del Reino Unido que tenga libros publicados en una editorial de género y en una generalista. Muchos han difuminado las fronteras, pero sólo él las ha destrozado. Algunas personas solo eran fans de su ciencia ficción, otros solo de su ficción literaria, pero muchos – entre los que me incluyo – eran fans de todos sus libros.

Iain Banks dejó tras él una obra envidiable, y sospecho que muchas de sus novelas permanecerán a la venta durante mucho tiempo. No leo un libro suyo desde hace unos años y planeo releerlos muy pronto. Sospecho que los releeré varias veces en el futuro.

Para celebrar el Boxing Day, aquí os he preparado un recopilatorio con todos los enlaces del especial dedicado a Iain Banks. Esperemos que hayais disfrutado tanto de él leyéndolo como nosotros preparándolo.

Para celebrar el Boxing Day, aquí os he preparado un recopilatorio con todos los enlaces del especial dedicado a Iain Banks. Esperemos que hayais disfrutado tanto de él leyéndolo como nosotros preparándolo.